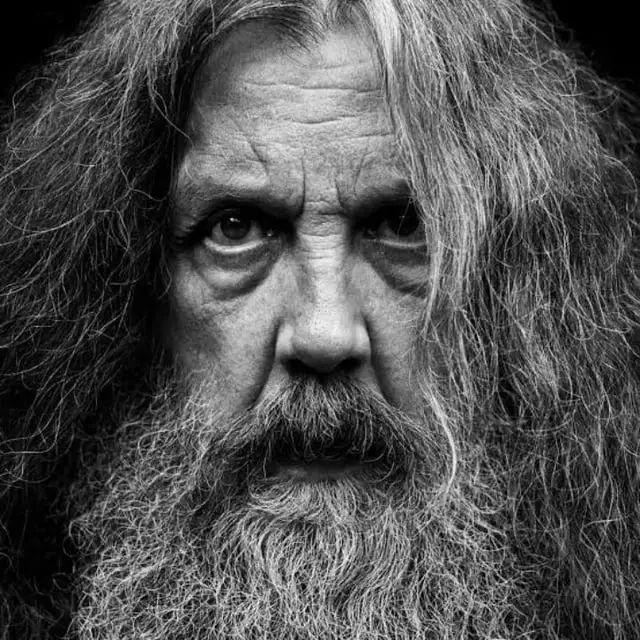

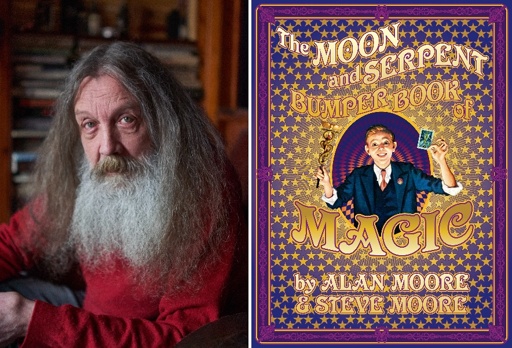

Many readers of Alan Moore—the prolific and influential author of Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Jerusalem, and, most recently, The Great When—are enchanted by the magic of his creative vision. For his next trick, The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, Moore would like you to come away with a respect for, and perhaps even a belief in, magic itself.

The 400+ page grimoire, coauthored with the late Steve Moore (no relation) and published by IDW’s Top Shelf Productions imprint, combines a lively and accessible history of ritual magic, practical guidance on how and why to use such techniques as tantra and Tarot, and amusing summaries of the lives of magical practitioners through the years—from Hermes Trismegistus to Alistair Crowley—done as single-page comics. Moore spoke with PW via email about the Bumper Book, magic, superheroes, and more.

…

On the matter of the comic strip medium and its possible links to occult consciousness, however, I think there’s a much stronger case to be made: I believe it was during the 1980s that a Pentagon study concluded that the comic strip medium’s combination of pictures and words in sequence was the most efficient way of passing on complex information in a way that was likely to be retained. Unsurprised, but wondering why this might be, it occurred to me that the image, being preverbal, is the prevailing unit of currency in what used to be called our right brain, while the word is the prevailing currency of what used to be called our left brain. Might it be that the way we read comic strips engages these two “halves” of our brain on the same task, both at once?

In the Bumper Book, we propose that it was representational markings, or imagery, that gave us the key to written language, which in turn provided the key to modern consciousness, which our gradually dawning minds interpreted as magic. I suggest that the comic strip form, used correctly, can be a near-perfect medium for transmitting magical ideas, a bit like the poetic “language of the birds” that the alchemists construed as the ideal way to communicate concepts pertaining to alchemy. After all, our earliest cave-wall comic strips were probably intended magically.

Historically and even today, most people’s conception of magic involves invoking supernatural forces to affect the outside world, and people typically either believe in it credulously or dismiss it as mumbo-jumbo. In The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, you make clear that the purpose and effect of these belief systems has mainly been to transform our inner selves and perceptions. How and why do you think these two distinct ideas got so muddled throughout history? Does magic have a PR problem?

…

Amidst all this, we felt that any real human importance or social use for magic was being lost in a sea of either fatuous make-believe or Master of the Dark Arts theatrics. So, with the Bumper Book, we wanted to present what we hope are lucid, coherent and joined-up ideas on how and why the concept of magic originated and developed over the millennia, a theoretical basis for how it might conceivably work along with suggestions as to how it might practically be employed—and, perhaps most radically, a social reason for magic’s existence as a means of transforming and improving both our individual worlds, and the greater human world of which we are components. And we wanted to deliver this in a way that reflected the colorful, psychedelic, profound and sometimes very funny nature of the magical experience itself. That, we felt, would be the biggest and most useful rabbit to pull out of the near-infinite top hat that we believe magic to be.